Sanders Research Associates energy analyst, John Busby, while attending the Sixth Annual International Conference in Cork in 2007 of ASPO, the Association for the study of Peak Oil and Gas, was struck by the presentation of Michael Dittmar, a CERN physicist working on the Large Hadron Collider, in which he highlighted the miniscule supply of tritium, one of the essential fuels for the fusion reactor.

The fusion reactor is promoted as the ultimate source of the world’s energy, based on the sun’s energy production by the fusion of hydrogen atoms, but does in fact rely on the fusion of deuterium and tritium. There are many perhaps irresolvable problems in fusion research, but as this article will argue, the impossible scale-up in tritium production from kilograms to tonnages, will prove to be its nemesis.

An anxious world, desperate to find a solution to an energy crisis, funds the research which it hopes will lead to the deployment of fusion reactors at the end of the century when but a modicum of fossil fuels will remain. Michael Dittmar believes this to be an illusion, a view shared by John Busby as he attempts to explain this complex subject.

Nuclear sustainability

With the reduction in demand post-Fukushima, primary uranium mining now provides around 90% of the fuel for the world’s fleet of reactors. The other 10% is from secondary supplies, formerly it was mostly from ex-military material but is now the products of recycling and from stockpiles built up in times of reduced demand. The price of tri-uranium octoxide (U3O8) known as “yellow-cake” remains low ($20 per pound U3O8, at end of 2016), because although a number of new reactors are under construction, the accelerating closure of old reactors has led to a falling in its demand, not lifted by that of the replacements. The nuclear contribution to world electricity generation fell to around 10% in 2016 (2616/24816 TWh), providing 3% of the world’s primary energy, but only 1% of it as electricity.

Although it is claimed that an endless supply of natural uranium exists in the earth’s crust, visions of sustainability lasting for “thousands of years” (sic) rely on the deployment of fast breeder reactors in which depleted uranium from the current fleet of “once-through” nuclear fission reactors is arranged as a “blanket” around a core of separated plutonium from spent fuel, highly-enriched uranium—or a blend of both as mixed-oxide fuel (MOX). Fresh supplies of plutonium arise in the blanket and have to be separated out to make a new fuel core charge.

The problem is that the most accessible and the most concentrated uranium ores are of limited occurrence and recourse was having to be made to the lower grades. The low price has led to the closure of the low grade mines. The mine with the ore of the biggest high grade occurrence in Canada, Cigar Lake, was disastrously flooded, but is now in production. The expansion of the Olympic Dam deep mine in South Australia as an open-pit, uneconomically below 350 metres of rock, has been abandoned.

The

manufacture of fuel for fast reactors, as well as MOX for the present

“once-through” modes requires re-processing of spent fuel, which was

performed at Sellafield in the UK, is performed at La Hague in France

and in Japan and Russia. It was prohibited in the US as a

non-proliferation measure. Sellafield has been a financial and technical

disaster, leaving a toxic legacy costing the UK taxpayer a fortune

for its clean-up. So fast reactors would require the augmenting of the

world’s inadequate re-processing capacity, an unlikely pursuit after

the failure of the UK complex at Sellafield and its costly

decommissioning. In any case there is no commercially available fast

breeder and the one fast reactor under construction in Russia is a

“burner” for reducing problematic radioactive elements in spent fuel.

The

manufacture of fuel for fast reactors, as well as MOX for the present

“once-through” modes requires re-processing of spent fuel, which was

performed at Sellafield in the UK, is performed at La Hague in France

and in Japan and Russia. It was prohibited in the US as a

non-proliferation measure. Sellafield has been a financial and technical

disaster, leaving a toxic legacy costing the UK taxpayer a fortune

for its clean-up. So fast reactors would require the augmenting of the

world’s inadequate re-processing capacity, an unlikely pursuit after

the failure of the UK complex at Sellafield and its costly

decommissioning. In any case there is no commercially available fast

breeder and the one fast reactor under construction in Russia is a

“burner” for reducing problematic radioactive elements in spent fuel.

The introduction of the fast reactor would require it to run in parallel with normal reactors to provide the depleted uranium from which the plutonium is separated. The replacement of the initial core charge of plutonium will require the fast breeder reactor to run from 10 to 20 years, so that its progressive introduction to provide the desired sustainability requires mathematical modelling, which would take into account the number of normal reactors needed to fuel the fast fleet. OECD/NEA admits that the modelling has so far not been attempted, making its claims of sustainability for “thousands of years” somewhat flawed.

So the vision of nuclear sustainability has transfigured from “fission” to “fusion”, which it is claimed will provide limitless clean energy with the aid of the processes of the sun. But the process promoted is not that of the sun, which is the fusion of hydrogen into helium, releasing its enormous amount of energy.

JET

and ITER

JET

and ITER

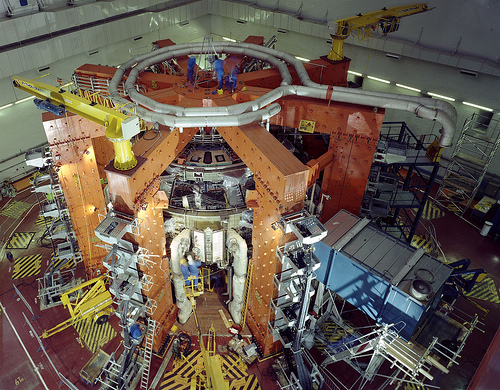

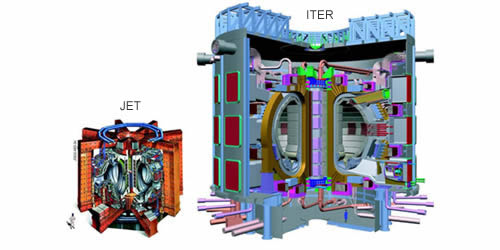

The Joint European Torus (JET) is located in the UKAEA premises at Culham, while its successor the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) is under construction at Cadarache in France.

The JET device is currently the world's largest Tokamak. [1] The JET facilities include plasma heating systems capable of delivering up to 30 megawatts of power. It has produced 16 MW of fusion power over 1 second’s duration, amounting to a liberated thermal energy of about 5 KWh, enough for a 2 bar electric fire (2KW) to run for 2 ½ hours.

JET consumes more power than it produces, but it is anticipated that ITER will do better with a number of incorporated refinements. ITER is expected to achieve a power output of 500 MW in 400 seconds pulses, compared with JET’s 16 MW for a few seconds.

As the materials employed in the construction of ITER are subject to irradiation and high temperatures, there is also a proposal to build an International Fusion Materials Irradiation Facility (IFMIF) to develop the new materials needed for it.

ITER, if successful, would be followed by the building of the first prototype power plant (DEMO) which will have to provide more power than inputted and at a steady state to be of any use.

Fusion problems

The sun emits energy by the fusion of hydrogen nuclei, forming a heavy hydrogen isotope called deuterium, this then fuses into helium while releasing an enormous amount of energy. It works because of the huge gravitational pressure in the sun which leads to a high density and temperature at the centre, maintaining continuous fusion.

In JET and ITER, the energy is produced by the fusion of deuterium (D) and tritium (T) in a mixture which has to be heated to over 100 million degrees centigrade. The heating is obtained by arranging magnetic forces which restrain the D and T in a toroidal field, producing a current in a plasma obtained from the ionisation of the gases.

- The first “challenge” is to extend the duration of the fusion from a few seconds in JET to around 400 seconds in ITER. This duration has then to be extended to a few decades in a commercial reactor. Some challenge!.

- The second “challenge” is to identify materials that will withstand the intense flux of the high energy neutrons leaving the plasma and bombarding the inner wall.

- The third “challenge” is to breed sufficient tritium in a lithium “blanket” surrounding the inner wall and to extract it and cycle it to the plasma to maintain the reaction.

- The fourth “challenge” is to remove the heat from the fusion by cooling circuits able to raise steam and drive electrical generators.

A schematic diagram of the D-T fusion cycle can be found on page 4 of at the following link.

A mixture of deuterium and tritium is drawn from a storage vessel to initiate the reaction. After some delay the tritium bred from the neutron bombardment of the lithium blanket will be cleaned and will replenish the storage. The initial charge will decrease the world’s constantly depleting inventory of tritium, so unless a recycling rate of at least 1 can be achieved, there will be a need for a continuous supply of tritium, as well as that for deuterium. The yield of tritium after what is essentially a chemical process would normally be less than one, so there has to be a gain of more than one in the tritium produced in the blanket.

Beryllium and lead act as neutron “multipliers”, so the proffered solution is to surround the plasma torus with a “blanket” of lithium/beryllium or lithium/lead alloys, the neutron bombardment of which it is hoped will breed sufficient tritium to maintain the reaction once it is initiated—for more than the few seconds the initial charge of tritium will allow.

Deuterium and tritium

Deuterium and tritium are hydrogen isotopes; hydrogen has but one proton, deuterium has one proton and one neutron, while tritium has one proton and two neutrons. Deuterium is found in ordinary water with a concentration of 0.02% per hydrogen atom. Heavy water, deuterium oxide, is distilled from water and gaseous deuterium then produced by electrolysis.

Tritium can be produced by the irradiation of lithium rods in a conventional fission pressure-water reactor core. The rods are removed during a fuel exchange and sent to a tritium extraction facility. However, tritium is mostly extracted from the Canadian CANDU reactors from the heavy water moderator. However, the world’s tritium inventory is only around 20 Kg and current production just about matches the deterioration, while to run just one 3000 MW (thermal) fusion reactor will require 167 Kg/year (without internal tritium breeding).

Thus, the fatal flaw in its introduction is that, other than for an experimental reactor, the commercial exploitation of the fusion reactor is inhibited by the paucity of the supply of one of the components of its fuel. The survival of the fusion concept now relies on a subterfuge: that it will breed its own tritium in the course of its operation.

Tritium supply

One tritium atom in a D-T fusion reaction produces one neutron and one neutron is then needed to produce a replacement atom of tritium from an impact with lithium. Not all of the neutrons emitted from the plasma will find the appropriate target lithium atoms in the “blanket”, so it is impossible without some augmentation for a cycle gain even approaching 1 to be achieved. In order to procure a gain of more than one, it is proposed that lithium is combined with beryllium or lead in the blanket, either of which act as a neutron multiplier when bombarded.

One proposal is for the blanket to be composed of porous pebbles allowing the produced helium to be released and for it then to act as a gaseous heat transfer medium to raise steam and drive a turbogenerator. An alternative molten salt heat transfer medium, a mixture of lithium, beryllium, sodium and fluorine has also been considered. The fusion fuels are thus deuterium, tritium, lithium and beryllium or lead and perhaps fluorine.

The blanket has to act as a tritium breeder, able to release tritium and helium so the tritium can be separated from the helium and mixed with deuterium to fuel the plasma and also has to act as a heat transfer medium. This complexity of purpose and composition provides the third and perhaps the most severe “challenge”—never to be met.

To put this into context, without breeding a 3000 MW (thermal) reactor would require 167 kg of tritium a year. A 3000 MW (thermal) fusion reactor is roughly equivalent to a 1000 MWe (electrical) fission reactor. Replacing the current fleet of over 400 fission reactors (which currently provide only 3% of the world’s primary energy) would therefore require the production of 67 tonnes of tritium per year..

An energy supply from fusion reactors capable of supporting the world’s economic activity, currently depending mostly on oil, gas and coal, would need to take into account the inefficiencies of producing hydrogen for motive power and would require around 2,000 tonnes of tritium a year.

In comparison, world tritium production is around 1½ to 2 kg/year, with a total world inventory of around 20 kg. So unless a tritium breeding cycle gain of at least 1 is achieved, there will be no fusion power. Even then each re-start of a fusion reactor would require an initial priming charge of tritium. If the inventory was just once exhausted, the world’s fusion fleet would stall.

Fusion diffusion

The findings of the world dynamics team enshrined in “The Limits to Growth” was that due to a progressive reduction in the concentration of resources there was a parallel reduction in the efficiency of capital resulting in a world economic collapse in mid-century, well before the ITER and its DEMO successor can be shown to work.

There is doubt that the so-called nuclear “renaissance” in fission reactors can be funded following the current credit famine, but the prospect of funding a fleet of fusion reactors constructed of the most expensive materials yet to be made must be dim, especially at the end of the century when the oil and gas and most of the coal needed to fuel the manufacturing processes for the construction of the fleet will be exhausted.

There is a paucity of nuclear physicists and engineers which is jeopardising the nuclear fission new build, let alone sufficient to staff the deployment of fusion power, even if it should prove to be a practical possibility, which is highly unlikely.

Perhaps a tritium producing process might emerge sufficient to fuel a number of reactors, but paradoxically its production by irradiation of boron in solution in fission reactors cooling circuits and spent fuel ponds is emerging as a serious problem. It is an ingredient in the stress corrosion cracking involved in the ageing process which has led to the replacement of around 200 major components of PWRs and BWRs. So in any process in which it is produced or utilised it has the propensity to ingress through the alloy steel grain interstices, contaminating reactor containments and groundwater. A commodity that decreases more than 5% a year, destroys its containment and makes its surroundings toxic is not an ideal fuel.

ITER

The “International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor” (ITER)

under construction at Cadarache in France, will however be fuelled with

a mixture of deuterium and tritium. Deuterium can apparently be readily

extracted from water, but tritium, like the fuel for a fast reactor,

originates from a number of fission reactors, mainly from the

heavy-water reactors in Canada. Also tritium is a radioactive isotope of

hydrogen with a short half-life of 12.3 years and deteriorates at more

than 5% a year and therefore has to be continuously produced and stored

for as short a period as possible.

Even assuming it could be made to work, the fusion reactor requires the continued running of the fission reactors it is supposed to supplant to produce its tritium fuel component. As a pilot plant ITER will undoubtedly experience a series of starts and stops and due to the very small initial amount of tritium available; it may well be used up in successive starts.

Even with the short plasma pulses, JET’s torus lining, similar to the tiling on the space shuttle, has been damaged by the heat and radiation flux. The ageing problem of fission reactor containments is far from resolution, especially for fast reactors. ITER’s internal surfaces will be subject to higher heat and neutron flux and its survival under operation is as unlikely as its tritium breeding cycle will sustain its operation.

There is considerable “spin-off” from basic research and much may trickle down from fusion research, which may well justify some level of public expenditure in evaluating plasma and tritium properties, but the suggestion that ITER can lead to a new dawn of cheap, limitless energy is an illusion. The proponents have described insurmountable problems as “challenges”; such is but playing with words. ITER simply is never going to work for more than a few seconds and (if allowed) will rapidly use up the world’s inventory of tritium. Its DEMO successor will never be built.

[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tokamak